Happy New Year!

This is always an odd week in the year. People get back to work but it often feels like an adjustment period before the real game starts again next week. Of course, for people looking after people who are unwell, working in any kind of acute services, that’s a luxurious state of mind they often can’t afford.

This is Water

This is not a post about the lack of clean water for people who inject drugs and how they end up using puddles, toilet water, or saliva as their water for injections. You can read more about that in this excellent paper. (What? You’ve not actually read it yet? Stop reading this immediately and first acquaint yourself with one of the best papers in recent years. I’ll wait.)

This post is about stigma which, on reflection, is related to the problem of accessing sterile water. Though, in truth, just about everything about drug policy has to be viewed through the stigma lens. In 2005 David Foster Wallace gave the commencement speech at Kenyon College in the USA. Foster Wallace killed himself in 2008 after a drawn out struggle with a major depressive disorder. You can watch the speech on YouTube

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

I tell this little parable quite often as I find myself increasingly drawn to Foster Wallace’s message. And, of course, the ‘water’ here is stigma.

We have become so accustomed to what we do in drug treatment circles that we barely notice the stigma. If it is any consolation, it is even less obvious outside and people who have never had anything to do with drug treatment swim around, utterly oblivious. Most recently, I used it to try and highlight the severity of the problem to medical students.

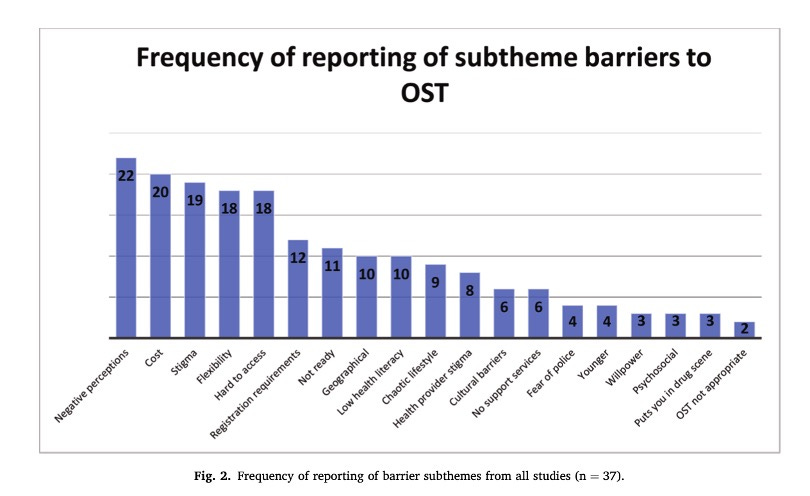

Last year, a systematic review of the barriers to opiate substitution therapy was published. And here is the figure showing the 19 sub-themes identified.

Now, here in the UK we are lucky enough to be able to ignore the ones around cost — at least in the sense of them being personal barriers experienced by individuals. There is a very reasonable argument that the inadequate funding of treatment services in the past decade (and longer) is a major barrier but that’s not what they mean by cost.

Note how stigma comes in third. I’d argue that many of the others are kissing cousins of stigma — surely “negative perceptions” is tied in? (Some are also related to payments in different healthcare system — drug treatment services may have been privatised a decade ago with serious consequences for the treatment system but we remain, at least for the moment, some distance from this in the UK.)

At this point, many readers will fling up their hands in horror at the thought they are stigmatising anyone. Some of my best friends are drug users. I’ve used. I understand and I am as far from stigma as is possible. It is everyone else… Here are some gently provocative questions:

What about putting people’s scripts on hold to encourage them to get in touch?

What about urine testing every visit, regardless of whether it is needed?

Have you ever seen a script being used to compel someone to do something — even, say, something like making them seek medical attention which is clearly in their own interest?

Have you ever been irritated at people not turning up for appointments or discharging against medical advice?

Anybody you’ve kept on supervised or daily pick ups as you think they will go out and use?

I would argue that all of these are stigmatising to some extent. Now the aim here is not to run a competition to find the most worthy person. Or to embarrass or shame anyone. In many circumstances, these actions could be justified, perhaps even perfectly reasonable for safety reasons and particularly when we are prescribing a controlled drug. My point is that in very many cases all of these will add to stigma. They just heap it on to people who already shoulder an outrageous burden.

A qualitative study of discharge against medical advice (DAMA) in the States looked further at why people were upping and leaving hospital despite serious medical conditions. (Spoiler: mostly stigma.)

The conditions really were serious with 15 out of 20 participants admitted with infective endocarditis. Endocarditis, untreated, has an eye-watering mortality and few people will recover fully, unscathed. There were important factors like boredom and social isolation — people who use drugs, especially people who inject drugs, rarely have solid social networks. There is not going to be a steady stream of visitors bringing grapes and word search books. They are not likely to have iPads or other devices to while away the hours watching Netflix. All of that could be fixed with some peer group support and a little effort.

Much harder is to get over the stigmatising approach of healthcare professionals. It’s likely their withdrawal may not have been managed well and their pain not well treated. Importantly, and I think this was a key finding in this qualitative paper, it only takes an isolated comment or glancing attitude to trigger people who come freighted with stigma. A single healthcare professional can undo all the work of a whole team who are dedicated to treating everyone with compassion and decency. The authors tell how one person, Dakota, felt “intense shame and embarrassment”:

So you know, I just, I left, and the first thing I did was went and got high, that night, as soon as I left. And it wasn’t, it wasn’t fair to the doctors that took their time out to make me better. It wasn’t fair to the nurses that didn’t, that did believe in me (laughs). Um, because of this one nurse, you know, I, I just felt like I wasn’t good enough, so I went out and got high.

The problem of stigma is well known.

What I want to highlight is that even though we are all hyper-aware of the importance it keeps creeping in and we need to be constantly vigilant; we have to keep questioning how we deliver services and how we can shape care that minimises the effects. It’s easy to let it wash over us and not act. Of course, we need to keep advocating for healthy drug policies at a macro level but we have to be aware of how clinical care can be easily twisted.

The one thing we can do is just try not to stop seeing the water and pause every now and again to question everything we do.

More to come…

If you enjoyed this post and would like to get future updates then please subscribe. It is free and updates will land, fuss-free, in your inbox.

If you already have subscribed — thank you! Why not bother the hell out of someone else and forward this email to them?

Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash

Stigma of folks with Substance Use Disorders. It is like a form of racism. Extremely harmful and unhelpful. Multifactorial. Multidirectional. Conscious and unconscious. But, like racism, it must be challenged at every opportunity. Education is important. And we need to start with the healthcare professions. And we also need to help our clients 'unlearn their self stigmatisation' that society has caused.

It’s only an impression but, when I have been locumming, I sometimes got the impression that some institutions had a slightly condescending approach to clients - and that individuals who did not adopt similar attitudes were frowned on.