OK, so I want to keep it lean this week and I have a little news about my new Twitter account and I've picked up on a paper that was published recently but didn't make the cut for Addiction Professionals’ Clinical Update.

Many thanks for the emails and comments on last week's post. I was keen to get something down on stigma quite early as it is a topic that needs to be constantly re-visited.

New Twitter account

I have a mixed relationship with Twitter. I deleted my account and left it completely for several years but, for various reasons, went back in 2020. (I’m weak.) I am often dismayed at the wretchedness of the interactions. There do remain glimmers of hope and I don't think that social media is fundamentally evil. I do think the way it is currently organised and structured is deeply flawed.

One of my personal difficulties has been having several different strands that interest me and trying to accommodate them in a single account. The favourite option seems to be to have a specific Twitter account that deals with drugs and drug policy. Which is a back-arsed and long-winded way of saying that Antidotum now has its own Twitter account.

You can find it at @TheAntidotum.

Hopefully, the focused nature of the account will encourage me to tweet and engage more — which is where I think Twitter can be incredibly valuable. All that said, I'm a huge fan of comments on posts as a way to engage about a topic without all the noise of social media. Keep 'em coming and I'll certainly reply to them all when possible.

Why are people dying?

So let’s take a brief look at this paper.

Causes of death among people who used illicit opioids in England, 2001–18: a matched cohort study. Lewer D, Brothers TD, Van Hest N, Hickman M, Holland A, Padmanathan P, Zaninotto P. The Lancet Public Health. 2021. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00254-1

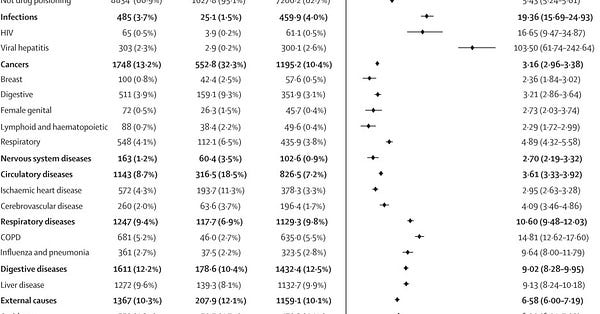

This, as the title gives away, is a matched cohort study and the researchers picked out patients in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink who had documented illicit opioid use. They then matched them up to a comparison group who were selected by age, sex, and general practice who had no record of illicit opioid use. They put this together with death statistics from the UK Office for National Statistics and used regression analysis to crunch the numbers.

Overall, they collected data for 106,789 people with a history of illicit opioid use who were followed up for over 8 years. They matched them to 320,367 controls who were followed up for a median of 9.5 years. They found that over 13,000 of the exposed cohort had died with a standardised mortality ratio of 7.72.

In other words, the risk of death is eight times higher.

The most common causes of death were drug poisoning (33.1%), liver disease (9.6%), COPD (5.2%), and suicide (4.9%).

There are a lot of numbers in this study and they need some picking out. Here are the most important things you need to know. The overall implications of the evidence is that the increase in opioid related deaths, that we've all known about, do not seem to be satisfactorily explained in the past 10 years purely based on the increased average age of the people who use drugs. The rate of fatal drug poisonings increased by 55% from 2010-12 to 2016-18. In just six years the increase was from 345 deaths per 100,000 person-years to 534 deaths per 100,000 person-years. You can’t explain that away as solely an ageing phenomenon in people who are just six years older.

This paper suggests something more was happening.

There is undoubtedly clear evidence of the increased number of fatal drug poisoning seen in this period. The authors are fairly careful in the paper itself to point out that an "alternative hypothesis" is needed to explain this rise in deaths. That’s the nature of academic writing for you but the good news is that the authors have more freedom to comment elsewhere.

There is an excellent short Twitter thread on the paper from Dan Lewer who is first author (a good example of how Twitter can work really well):

Dan also went further with his comments in the national media and that's because it is blindingly obvious. It is almost impossible to imagine that the decline in the provision of treatment for people who use drugs isn't a major factor here.

I’m inclined to agree with him.

And, if I may allowed to trot out my personal hobby horse, Dan also included this comment on his Twitter thread. The population is older and that remains an important factor. Particularly when access to healthcare is so dismal:

Yup. And, stand by, as this is something I plan to go on about a lot in the future — the fragmentation and competitive re-tendering of services has had a key role in atomising care. The new Drugs Strategy has some impressively large numbers in promised funding but we shouldn’t forget just how far we tumbled in the past decade.

More to come…

If you enjoyed this post and would like to get future updates then please subscribe. It is free and updates will land, fuss-free, in your inbox.

If you already have subscribed — thank you! Why not bother the hell out of someone else and forward this email to them?